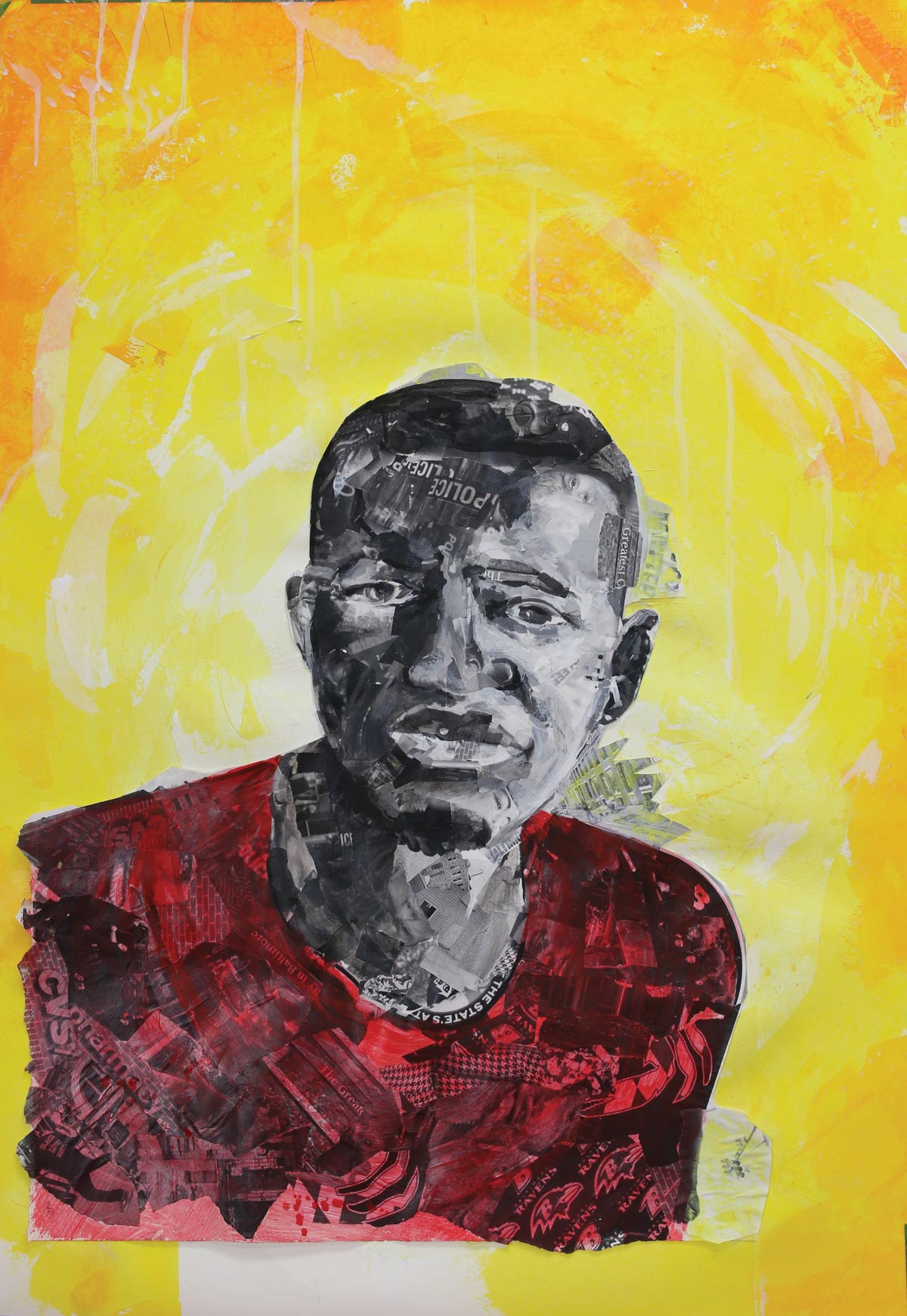

The Running Man

When all else failed, Freddie could run.

As a boy facing long odds in school and life, he would outrace friends on the football field and blow by them on the basketball court. As those odds played out when he was a young man, when he dealt drugs and made himself a presence in West Baltimore’s streets, projects, and alleyways, he’d run from the heat.

Freddie’s strategy—leave them grabbing at air—didn’t always work. He was arrested a dozen and a half times. But movement is freedom. Without fail, he’d run.

So when, on a sunny spring Sunday morning at the corner of North and Mount, right outside the King Grocery Mart where Freddie Gray often hung out with his boys despite the “No Loitering” sign, he and a Western District police lieutenant riding a bike toward the corner from the east briefly locked eyes, Freddie was off. The bike cop, who’d been riding in formation with three other officers, took off in pursuit.

Westward a half block to Bruce Street, no more than a tree-shaded alley decorated with trash, where he turned left. Galloping past a rolled-up carpet, old tires, a sofa. Flying past the seven houses on the west side of the next block down, five of them boarded up. Skirting the grass lot with the signs banning pets and ball playing. Across Presbury and into Gilmor Homes, a drab, low-rise housing project, where he entered a walkway called Bruce Court and pulled up.

“They weren’t going to catch him—Freddie was fast, man. But he surrendered anyway, just stopped right here,” says Kevin Moore, who points to a spot right in front of his apartment. “People talk about his asthma, and he always smoked those Black & Milds, but it never affected his physicality.”

Several of the pursuing police officers corralled Freddie. Officers searched him and found a spring-loaded pocket knife, the legality of which is still in question. It was enough to bring a charge, however. They carried Freddie to a squat stone wall where Presbury meets Bakbury Court, a carbon copy of Bruce Court a half-block over. More police arrived in cars. This is where Moore pulled out his cell phone, followed the scene, and recorded the images that traveled around the world.

“He didn’t weigh more than a buck twenty-five, and they was just throwing him around,” adds Mike Coner, Moore’s next-door neighbor.

Not more than a week earlier, Moore and Gray ran into each other and joked about “hooking up in prison.” Now, Freddie was face down on the sidewalk and on the verge of becoming a statistic.

After he died a week later, his spine mangled, his name would assume a place at the center of a chain of events that would rock the city: accusations of police violence, protests, riots, curfews, standoffs between citizens and police, the charging of six officers with crimes relating to Freddie’s death, a $6.4 million city payout to his family, and a national conversation about abusive policing and its effects on young men like Gray.

“There are thousands of Freddie Grays in this city,” says Warren Brown, a well-known criminal defense lawyer in Baltimore who has represented a few, though not Gray himself.

Friends and neighbors say he was a regular guy they called “Pepper,” though no one seems to know why. He was a joker—generous, respectful, easygoing, liked to get high. He preferred name-brand designer clothes, nice wheels, pit bulls, hot girls. His short life left us little more than that, and yet it has become a prism that reflects every ill that plagues this city. Crushing poverty. Fatherlessness. Joblessness. Childhood lead poisoning. Housing segregation. Police brutality. The endless street-to-jail cycle and the war on drugs that feeds it.

Whether you empathize with Gray and his messy race with life, or see him as a serial lawbreaker who shares responsibility for his fate, it is a Baltimore story. Freddie Gray was a scion of the city. He was raised on its streets, poisoned by its homes, educated in its schools, and then—allegedly—killed by its police officers. His was a life wholly shaped by the forces that act upon thousands of other young people here, and it bears a closer look.

It’s no longer easy to get a clear picture of Freddie Gray. As the legal drama surrounding his death proceeds, members of his immediate family have been largely shielded from the media by Billy Murphy, the attorney who negotiated the settlement of their civil brutality case against the city. Several did not answer a reporter’s calls or visits for comment, and Murphy declined to speak on the record. Police officials and leaders of the police union refused to comment on the specifics of Gray’s case, citing the pending case against the six officers involved.

But here’s what we do know: Born several months prematurely along with a twin sister, Fredricka, at Maryland General Hospital twenty-six years ago to a mother who had been addicted to heroin, Freddie Carlos Gray Jr. grew up in slum houses in Sandtown, just a few blocks from where he was last arrested. Gray’s father, Freddie Sr., didn’t live with Freddie, Fredricka, or an older daughter, Carolina.

Before Freddie and Fredricka turned three, their mother, Gloria Darden, filed paternity suits against Freddie Sr. He signed off on papers stating he was the twins’ father and agreed to have $40 of his wages from a job at Johns Hopkins Hospital garnished weekly for child support.

Money was always an issue for the young, broken family. Darden, who has said she couldn’t read, had been expelled from middle school and lived on a disability check. Former neighbors say that Richard Shipley, the man she lives with now, sometimes worked in construction. At least once, when Darden was in drug treatment, their home was without food or electric service, according to court records. By the time the twins were three, Child Protective Services had become involved.

Despite their troubles, neighbors say that Darden and Shipley, who assumed the role of the children's stepfather, did what they could to keep the family together. But the children were subject to a variety of predators, ones they couldn’t run from. At least one of them was sexually abused by someone outside of the immediate family, according to a lawyer’s testimony in an unrelated case.

Then there were the walls that closed in on Freddie and his sisters. The first six years of the twins’ lives were spent in homes that shed lead paint like dandruff, so the children could eat it, suck it from their hands, or breathe in its dust. From the time Freddie was two, the family paid $300 a month for a house on North Carey Street where, they said in a court deposition, paint flaked from window sills and the walls of bedrooms and hallways.

At one point, the Gray children each had lead levels in their blood that were more than seven times greater than what the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) say can cause brain damage. In the years Freddie lived there, his blood maintained a level that was at least twice the CDC threshold. He was one of more than 65,000 Baltimore children found to have dangerously elevated blood-lead levels between 1993 and 2013, a rate considered one of the highest in the nation.

Owned by Stanley Rochkind, an oft-cited inner-city landlord, the Carey Street house was home until 1996, when the family is believed to have moved one block north.

Neighbors remember young Freddie as a playful, agreeable kid. “I was devastated, I was numb to hear what happened to him,” says Rosalind Brown, who lived two doors down from the family, then moved into their Carey Street home two years after they left. “He was a nice boy, always smiling.” She raises her ten-year-old grandson Dominic in Freddie’s old house, and the child attends Eutaw-Marshburn Elementary School, next to a playground recently dedicated to Gray in Upton. The house is safe now, she says: “They painted it up real good.”

Freddie was a thin, smallish boy who would later play wide receiver in a local football little league. Sports were a refuge for him, remembers another former neighbor, Will Tyler: “It was something to do besides run the streets.”

After Freddie entered school, he was diagnosed with ADHD, was often truant, and, along with Fredricka, attended special education classes. The pair exhibited behavioral problems. Freddie failed several grades. Although some published accounts say he graduated from Carver Vocational Technical High School, the nearly all-black public school that serves the neighborhood, it appears Freddie actually dropped out in ninth grade. High school graduation was a criterion for successfully completing one of several stints on probation. There’s no evidence, at least in the court record, that he met that requirement.

The long-term impact of the Gray children’s lead exposure would play out in court a dozen years after they moved out of the Carey Street house. In 2008, the office of local attorney Evan Thalenberg filed a lead paint lawsuit against Rochkind on the Grays’ behalf, asking for a combined $5 million-plus in damages, nearly $2 million for Freddie. The suit alleged that lead poisoning from living in the Carey house resulted in “permanent and severe brain injury” to all three siblings and “will prohibit the Plaintiffs from gaining in any painful [sic] occupation, activity, or pursuit, as well as from performing any duties requiring the full and normal use of their mind, body, and limbs.”

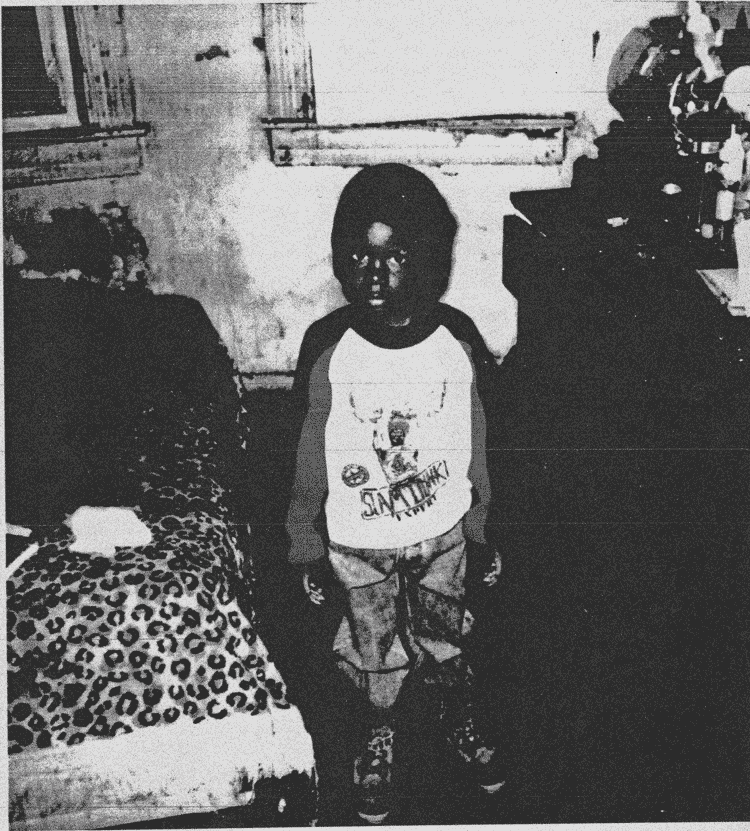

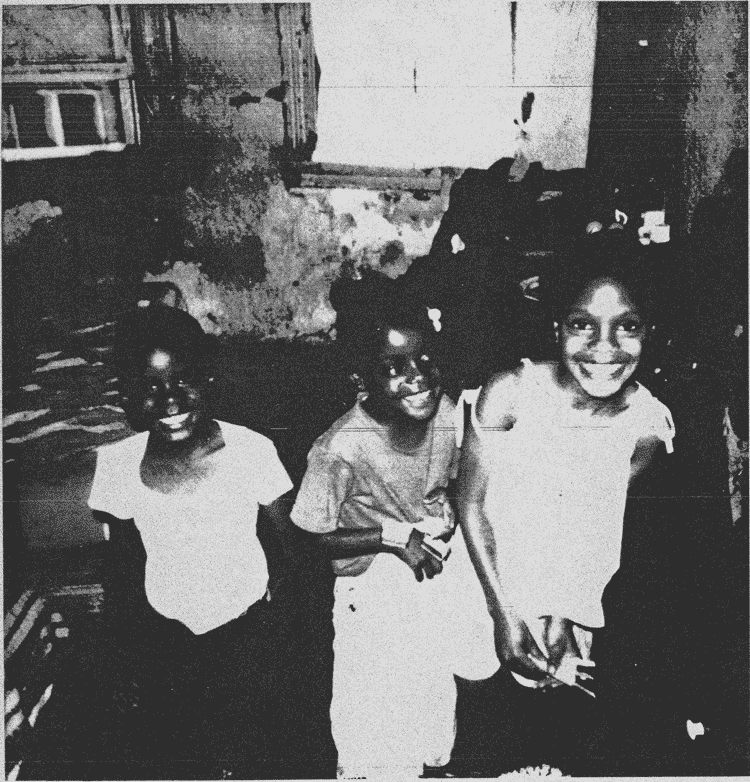

The children had been treated at the Kennedy Krieger Institute, sometimes as inpatients. Pictures presented as evidence in the lawsuit show a smiling four-year-old Freddie with his sisters against a backdrop of almost-bare walls—he looks both happy and doomed.

But the child in that photo was long gone. The twins were eighteen when their lead-poisoning case was tried, and both were incarcerated by that time: They had to petition the court to allow them to wear “civilian clothes.” (The charges against Fredricka would ultimately be dropped.) Freddie, after saying his piece in court, went back to jail, a place he would become too accustomed to.

A Baltimore childhood: Family photos of Freddie Gray and his two sisters were submitted in the family’s lead poisoning lawsuit in 2008.

Gray and his sisters all tested positive for greatly elevated levels of lead in their bloodstreams, which can cause severe brain damage.

Photo credit: Family photo from court filings

“He had charisma. I could tell by looking at body language. People walked behind Freddie, not alongside him.”

Bail bondsman Quintin “Toak” Reid knew Freddie well.

How closely could Freddie’s consistent criminality—his rap sheet shows a break in the flow of arrests only during times when he was jailed—be linked to the developmental impact of lead-tainted blood?

Social scientists and criminologists have long posited that there is a direct link between childhood lead exposure and crime: Just as higher blood lead levels have been associated with lower IQ and struggles with learning and behavior, they also correlate with higher rates of arrests for adults, several studies have found. And lawyers who tackle the cases of inner-city young people say their clients often bring up this connection.

“I’ve asked many of my clients, ‘Why do you have this problem? Why did you drop out in eighth grade? Why do you have this lengthy arrest record?’” says Jill Carter, a state delegate and defense lawyer. “Way too often, they’ll tell me they’ve been lead-poisoned.”

While his neighbors say that Gray showed few signs of impairment, one lawyer who defended him in court says the effects were manifest. “It was clear to me that there were some lead issues,” says the attorney, who did not want to be identified. “His reading and writing weren’t good. He wasn’t unintelligent, but you wondered just how far he could go.”

A bail bondsman the family hired to bail Freddie out of jail said he’d have to read the charges when Freddie stumbled over them. “He couldn’t make out words like ‘eluding’ or ‘fleeing,’” says Quintin “Toak” Reid. “He had a lot of street smarts, though. He was just trying to survive out here. People feel like they can take care of their families at age sixteen by selling drugs. That’s all they can do.”

And Freddie knew his neighborhood: Sandtown-Winchester, home to around 8,500 people in a Census tract that is one of the city's poorest. It’s also one of the tightest. “Everybody here is cousins, almost literally,” says Reid. “This is the wrong community for something like Freddie Gray to happen because they take care of their own here.”

Though Freddie was known as “Pepper” on the street, he was just as often called “Nephew” or “Cuzz” in the neighborhood. Mike Coner called him “Nephew” because his nieces went to school with Gray. In turn, other neighbors say, Freddie called them “Big Daddy,” “Mama,” or “Uncle.”

“Uncle” Will Tyler qualifies as a street relative because Freddie knew his daughter, Aaliyah. Tyler runs a nonprofit that organizes basketball tournaments and other athletic events for Gilmor Homes youths. “I give kids a place to go,” he says. “They haven’t had one for a long time. They’re tired of their illegal activities, of being arrested all the time.”

As a young man, Gray would take part in basketball round-robins that Tyler put together, playing a variety of positions with daring and skill. “He was a good kid who did what kids do,” says Tyler. Gray had a bit of gumption, he adds—he talked about going to community college, maybe even getting a job in law enforcement. “He wasn’t lazy. He had a thing about himself. I always told Freddie he could get a job if he worked at it.”

Tyler lives at Gilmor Homes’ southern side, several blocks from the site of Gray’s last arrest. There’s a balloons-and-bottles monument to a recent victim of Sandtown’s violence nearby, on Mount and Presstman, and plenty more as you head north. Mount and Baker. Mount and Presbury. 1827 North Mount. Around the corner at North and Carey. Even without the three shrines to Freddie in and around Gilmor’s northern end, and the scores of dead-eyed vacants and yawning lots, it’s like wandering through a cemetery.

Yet this place was Freddie’s life, where he hung out, helped out neighbors. And, if his criminal history is to be believed, it’s where he plied his trade.

Freddie’s record as a juvenile offender, if there is one, is not available to the public. But his advent into adulthood suggests that he had already embarked on a budding career as a corner boy, a street-level drug dealer. A week after he turned eighteen, when he became an adult in the eyes of the law, he was arrested for dealing heroin and lying to police. Four days later, another arrest. The next day, another bust for drug dealing, for which he’d serve a few months of hard time, and receive a suspended three-year sentence, which he’d spend instead on supervised probation.

In all, Gray would be arrested at least eighteen times before his death. At one point, he had been busted at least eleven times during one period of probation. Almost all the charges were drug-related, usually just-large-enough amounts of heroin and cocaine to be hit with distribution charges. A few were typical “nuisance” complaints—playing dice, hanging out in a vacant apartment. His only violent charge occurred about a year before his death, when he was accused of hitting an acquaintance.

Freddie may have been in trouble a lot, but Tyler says he did what he could to brighten things up in the neighborhood. “I last saw him four days before [his arrest] and he was playing jokes on his friends,” he adds. “You never felt threatened by him.”

Big Daddy—aka Earl “Manny” Williams—says Freddie would spread his money around. “I’m not going to say Freddie was a saint because he wasn’t, but he had a good heart. He’d look out for people, buy them groceries, that kind of thing,” says Williams, who watched Freddie grow up “chasing his friends around the neighborhood.”

“He had charisma,” Reid adds. “I could tell by looking at body language. People walked behind Freddie, not alongside him.”

Another Mount Street denizen, Alethea Booze—“Mama” to Freddie—says he would make sure older neighbors had what they needed. He’d walk by her stoop with his buddies on his way to King Grocery and ask her if she needed ice cream or a soda.

“When he’d have money, he’d buy some of the kids new tennis [shoes],” Tyler says. “He understood that the peer pressure is crazy around here. You don’t come up with the best clothes or tennis, you won’t be running with the hip crowd.”

The cash, or some of it, came from the monthly “lead checks” he started receiving at age twenty-one in 2010, when the lead paint lawsuit against Rochkind produced enough evidence to encourage his lawyers to settle. Though the terms of the agreement were sealed by the court (and attorney Thalenberg didn’t return calls), it’s clear that each Gray sibling received a sum well into six figures, at least. Spread out over many years, such settlements may come to only a few hundred dollars every month, but they do guarantee regular income.

In 2013, however, Freddie traded in a considerable part of his lead settlement for a smaller lump sum. An August Washington Post investigation found that the Gray children sold off their rights to future payments to Chevy Chase-based Access Funding, a company that markets to lead poisoning victims and offers immediate payouts.

The sisters relinquished $435,000 in long-term checks for a one-time-only check of $54,000—about 20 cents on the dollar. Freddie sold $146,000 in future guarantees, worth $94,000 at the time, for around $18,000.

“He wanted more than this, but he couldn’t leave us. This was his place. This is where he belonged.”

The witness: Kevin Moore shot the video of Gray’s arrest.

Up on Bakbury Court, a group of young men sit on stoops on a hot weekday and reminisce about Freddie. They say he had the money to strut around. He liked the big brands—Gucci, Prada, 7 for All Mankind, True Religion, Under Armour, Louis Vuitton—and expensive sneakers. Though he always walked when he was in Sandtown, friends say he often had wheels—a van or two, plus, depending on who you talk to, an Acura, Cadillac, or Lexus. Smoking some good weed, maybe guzzling a “Gatorade”—a concoction that includes the central nervous system depressant GHB—got him through the night.

Did Gray have a drug habit? About a year ago, he was arrested for possessing a few oxycodone tablets. Several of his busts for distribution were for a relatively small amount of drugs—a possible sign that he was selling to pay for drugs for his own use. Along with evidence of marijuana use, the medical examiner found opiates in his body.

But several people who claim to have known him say Freddie dealt drugs for the income, and to help out his family. One young man, who refused to give his name “because police will come after me,” says he last saw Gray on the morning of his arrest. As usual, he had started his day early. “We’d get going at six in the morning,” he says. “We’ve got a job to do too, you know.”

One of the Bakbury guys shows a picture on his phone of Freddie mugging with arms spread, in front of four friends, taken almost on the same spot of his final arrest and just a few days before, looking like he couldn’t be more at home.

When Freddie took off on the morning of April 12, he ran toward the only refuge he knew. “He was trying to get back to the projects,” Reid speculates. “Once you’re there, you’re safe. A lot of those doors are unlocked. He could jump in, lock the door behind him. There’d be a lot of people who wouldn’t think twice about helping him.”

Even though his mother and sisters lived in better neighborhoods—Belair-Edison and Harwood, respectively—Gray never really left Sandtown. He always ended up back around Gilmor Homes.

“He wanted more than this, but he couldn’t leave us,” Kevin Moore says. “This was his place. This is where he belonged.”

He and Moore would often ponder what a new life outside the neighborhood might look like, Moore recalls. “We all want to get out of the projects. We’d talk about what it would be like to get out of Baltimore. But he died. It never happened.”

Up to the end, his neighbors kept an eye out for him.

Alethea Booze was in her kitchen on April 12 making turkey wings, greens, and mashed potatoes for when her family got back from church. She heard someone yelling down the alley. Because she had suffered a stroke and had trouble walking, she had her friend Robin help her down past six houses and an empty lot to see what was going on. She saw Moore and a young woman taking video of someone on the ground. Freddie. No surprise there. “I’d seen them chase him several times,” she says.

Gray was yelling in pain as one officer put his knee on the back of his neck and another pulled his legs up behind his back. Williams says, “They had him in the Boston crab”—a wrestling hold. Police started dragging Gray to a paddy wagon as he screamed in pain. “We said, ‘His legs are broke! Take him to the hospital!’” Booze recalls. “A black cop was there. We asked him, ‘Can’t you do something?’ But he walked right by.”

Gray was put in the van, still yelling, but not buckled in. The vehicle lurched off toward the Western District police station, six blocks south, maybe a minute and a half away. It arrived forty-six minutes later, after several stops. Somewhere along the way, Freddie Gray sustained the spinal cord injuries that would kill him.

“Freddie was just like a lot of guys here,” Booze says. “But he would always stop and ask me if I was doing OK. Now, his little friends do the same.”

“I feel like I need to apologize, even if it's something that happened twenty years ago,” says Major Sheree Briscoe, who just took over the Western District.

Nowhere to run: Sandtown-Winchester resident Nathaniel Silas in one of the the troubled neighborhood's alleys

In May, an investigator from Baltimore City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby’s office visited Sandtown to learn the circumstances surrounding Gray’s death. The investigator dropped by Mount Street and talked with Earl Williams, who told him to go back outside, lean against his car, and see what happened. Within minutes, Williams says, an officer in a passing cruiser yelled at the investigator to get off the street.

The irony is that Mosby’s office had earlier in the spring asked for police to crack down on street activity—thus contributing to the heavy-handed style of policing that residents say they have long endured. The toll of street arrests, whether successfully prosecuted or not, can be devastating: Those with police records are half as likely to find a job as those who have never been arrested, researchers have found.

This incarceration cycle runs rampant in places like Sandtown, which sends more people to jail than any other Census tract in the state and where one in four juveniles has been arrested—double the rate elsewhere in the city. “[Police] treat the courts like a dumping ground and make an ever-increasing percentage of the population unemployable,” argues defense lawyer Warren Brown. “We need a Marshall Plan for these parts of Baltimore. What are the plans for uneducated, unemployed people here for the next ten to fifteen years? They’re treated like the nuclear waste from power plants. They’re contained. The police are charged with enforcing that containment.”

A. Dwight Pettit, a defense attorney who also has filed brutality lawsuits against the police, echoes that position. “I’ve seen questionable searches and seizures triple in the last ten years,” he says. “People are running from police because they can’t afford $50 for bail, whether they are guilty of a crime or not.”

Even older Sandtown residents, who often lament that succeeding generations haven’t found real work and bring gunplay to the neighborhood, say that younger men face indignities at the hands of law enforcement that they never should have. Around the time of Gray’s arrest, it was routine to see police jack up people on corners, Booze says. “Then, they’d pull their pants down in front of the public to search them, or Taser them, or throw them on the ground,” she says. “They were getting away with murder the way they treated people.”

In late May, Major Sheree Briscoe took over the Baltimore Police Department’s Western District, blocks from the worst of the rioting that flared in April. A Baltimore city native and a City College grad, Briscoe now shoulders the formidable task of repairing the frayed relationship between this community and police after Gray’s death. She takes what she calls “intentional community walks” in uniform: With her close-cropped hair, strong build, and bolt-upright posture, she cuts a warm, yet imposing figure, a combination of maternal care and no nonsense.

“When I look around Sandtown, I see a lot of nice people,” she says. “A lot of people gather on the corners just to meet. Others are doing something else. It’s our job to separate that out.”

How her officers do that job, Briscoe says, is changing here in what is often called the post-Freddie-Gray era. Besides introducing herself to people, she and a police captain look for housing and business code violations. They report trash heaps and overgrown lots and hand out quick-reference guides to city services. They remind people they’re entitled to those services. And they do social outreach, helping people with mental health issues and getting to know those who hang on corners.

What she’s describing represents a dramatic shift from the aggressive, zero-tolerance model to a more holistic style of “community policing.” But this is a community that may be a skeptical partner. “It’s not popular to be seen holding hands with the police right now,” Briscoe says.

Not that it ever was. Generations of distrust have built up in neighborhoods like this. “I need to be sincere with people to make these relationships grow,” Briscoe says. “We’ve been talking to people who’ve had trouble with the police. I feel like I need to apologize to them, even if it’s something that happened 20 years ago.”

The guys on Bakbury Court aren’t impressed—“police is police,” one says. But Earl Williams and others have seen improvements in how the force treats the community since Briscoe’s arrival. “She comes to whatever meeting she’s invited to and listens,” Williams says. Cops have taken a noticeable step back from the aggressive approach of clearing corners, and there’s a bit more breathing space. “Things are different now. I haven’t seen anybody chased in a while.”

The death of Freddie Gray—and the groundswell of protest following it—has fed the momentum behind a host of criminal justice reforms. State laws that went into effect in October allow people arrested but not convicted of crimes to expunge their records. Petty marijuana convictions can now be wiped clean as well. A Second Chances Act shields nonviolent misdemeanor convictions from public view after a three- to seven-year period, giving offenders a better shot at finding jobs. In August, the state’s Department of Justice issued new law enforcement guidelines that strongly condemn racial profiling by police, making Maryland the first state to follow the federal guidelines banning discriminatory profiling issued in December 2014.

City officials are looking to extend the Safe Streets antiviolence program to Sandtown. Based on the principles of violence interruption pioneered by Chicago’s CeaseFire program, Safe Streets employs former offenders to defuse neighborhood disputes before they escalate. The program has been shown to be effective in lowering gun violence in several sites in the city, including McElderry Park and Cherry Hill, but it’s also been rocked by troubles, most recently in July when police found guns and drugs stashed in the McElderry Park program site office.

A constellation of programs, conferences, classes, and seminars now carry Freddie Gray’s name, all part of the citywide conversation about what needs to be done to change the circumstances under which he lived. His long-troubled neighborhood is the focus of renewed redevelopment attention . At the University of Maryland School of Law, a new course called “Freddie Gray’s Baltimore: Past, Present and Moving Forward” is scheduled to become an ongoing part of the curriculum.

The school has expanded its work in West Baltimore in the past year, connecting with nonprofit groups and a student bar association to teach kids from four urban high schools their legal rights. In June, more than fifty sat in while Marilyn Mosby and others told them about their constitutional protections; a separate program led by law students holds workshops for middle school kids on freedom of speech.

Freddie’s old bondsman, Toak Reid, says he’s getting involved with the law school’s efforts to inform kids of how to behave when police officers confront them. It’s no fix for the real issues that led to Gray’s death. But it might help save a few lives. He wants to reach a new generation of West Baltimore schoolchildren, he says. “So they don’t run like Freddie did.”