Why Local Media Matters

We were expecting a quiet day on Monday, April 27. Virtually everyone on staff at City Paper, the free weekly newspaper where I was editor at the time, had chipped in to report on the protests that began soon after Freddie Gray was taken into custody on April 12 and brutally injured while in police custody. The protests escalated after Gray died of his injuries on April 19, and much of the staff, including myself, was at the protests on Saturday, the 25th, which extended into confrontations between protestors and baseball fans outside Camden Yards, along with the destruction of several storefronts and at least one police car.

But Monday was the day of Freddie Gray’s funeral, and the family had asked for calm. So we figured we’d be able to focus on wrapping up our weekly issue—which goes to the printer on Tuesday morning. We had reports on Saturday’s events and speculation about the fate of the police officers involved in Gray’s arrest and transport.

Just after noon, we got word that several downtown institutions, including the University of Maryland, Baltimore and Baltimore City Community College, were closing early, at the recommendation of the police. We had seen flyers circulating on social media about a so-called “purge,” a reference to the movie The Purge, about a day of lawlessness, that I had to look up on Wikipedia, fuddy-duddy that I am. But we took them to be typical teenage posturing. The Baltimore Police Department, apparently, did not.

At about 3 p.m. I got a call from a freelancer near Mondawmin Mall, reporting that the area was surrounded by dozens of police in riot gear. Then-managing editor Baynard Woods and photo editor J.M. Giordano went to the scene. Woods and Giordano in particular had been covering the protests relentlessly, getting to know sources among the activists—an effort that started when they covered the local Ferguson-related protests in 2014—and the residents of Sandtown, where Gray lived and was arrested. For hours, they and others remained on the scene at Mondawmin and elsewhere around town as the violence escalated.

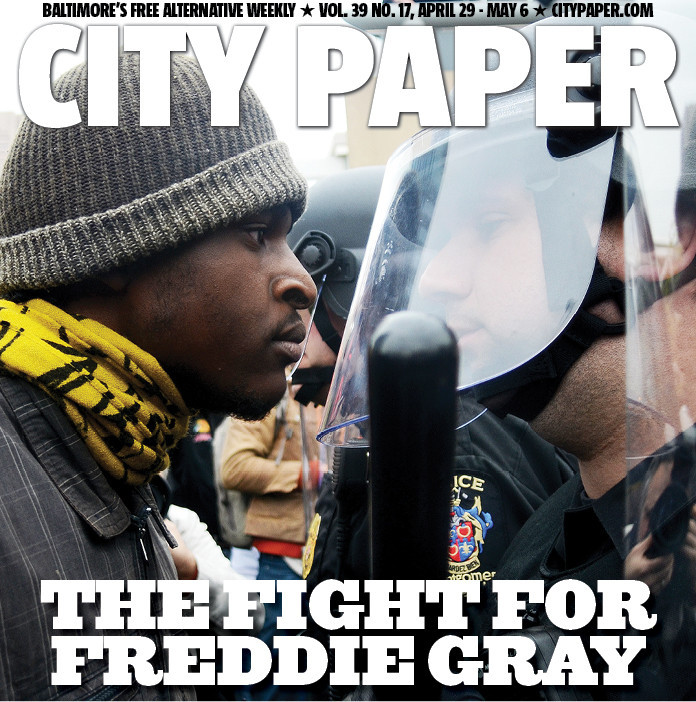

At some point, we had a decision to make. Should we close the completed issue as planned or tear it up and work all night to turn out a new one? Buoyed by the passion of a young, energetic staff with an earnest belief that they had a duty to Baltimore, we opted for the latter. We ended up with a new issue with dispatches from the protests and the riots, and a new cover with the headline “The Fight for Freddie Gray.” We left the office after 7 a.m. and chuckled as the security guard insisted on escorting us to our cars, despite the fact that the streets were deserted.

In the days that followed, we watched with the rest of the world as CNN, Fox News, and all the other national outlets rolled into town with their bodyguards, pre-scripted understanding of events, looped footage of fire and mayhem, and live reports staged to look like they were amid a war zone. Any local reporter or bystander will tell you that pretty much on every day after the violence of April 27, the media outnumbered protestors, police, or anyone else at the corner of Penn and North. As a result, millions around the world have a false understanding of what happened in Baltimore in April and May. They imagine hordes of angry black mobs and days of fire, looting, violence, and murder. I know from conversations that lots of Baltimoreans have similar impressions.

The truth is that there were weeks of organizing, protests, and marching involving thousands of Baltimoreans and the creation of what many hope will be a lasting social movement for change. These weeks of peaceful protest and organizing have been dubbed the Baltimore Uprising. It was interrupted by one day that included violence perpetrated by, at most, dozens of people. Thankfully, no one died in the violence, though protestors and police were injured and several businesses were damaged. Whether this violence was justified is a question for another essay. The point is that those hours of violence overshadowed weeks and months of protests that continue to this day, thanks largely to the national media presence. And that is a genuine shame.

Over those days, reporters for the Baltimore Sun, City Paper, WYPR, and some other local outlets were pretty much the only source of context amid the distortions. Over and over again, we heard from local people and people around the country, thanking us for presenting a clearer picture of what was happening, with background, history, and insight only gained from living in a city. I know reporters from the Sun and other sources received similar thanks, and they deserve it. It’s no secret that print media has been hit hard by sinking ad revenue and seemingly endless newsroom layoffs, along with corporate consolidation that has a few companies controlling the news spigot in a given town. Tribune Co., which owns both the Sun and City Paper, likes to brag that a single corporation controls more than 90 percent of the audience in the Baltimore market. Those newsrooms are filled with hard-working, passionate journalists doing the best they can with meager resources. And it’s worth pointing out that, even as crowds of citizen journalists replace professional ones, most of the in-depth, investigative reporting still comes from these embattled newsrooms. Who, if anyone, will continue this work when they disappear, and what will the consequences be if the answer is “no one”?

A week or two after the violence of April 27, the national media moved on, leaving Baltimore as GOP presidential candidates’ unfortunate shorthand for urban violence, even when it makes no sense. And yet, local reporters are still here, still fighting their way into the national conversation, still trying to paint a more accurate picture of events on the ground. Sometimes it seems like a futile effort—and maybe overall it is—but for the people looking to understand the dynamics of events in our city or to make positive, lasting change, it might be essential. It’s worth doing and supporting just in case. What’s the alternative?